Things naturally happen

Travel notes from Hokkaido

As a recent graduate of Boston University’s MFA program in creative writing, I had the opportunity to embark on a travel fellowship to work on writing projects abroad. So, after finishing my final medical school rotations in St. Louis, I departed for Japan on February 26th.

My goal was to travel from north to south across Japan’s islands, catching as many of the seasonal variations as I could. That meant starting in Hokkaido, in the north, where I suspected I would get to see some snow.

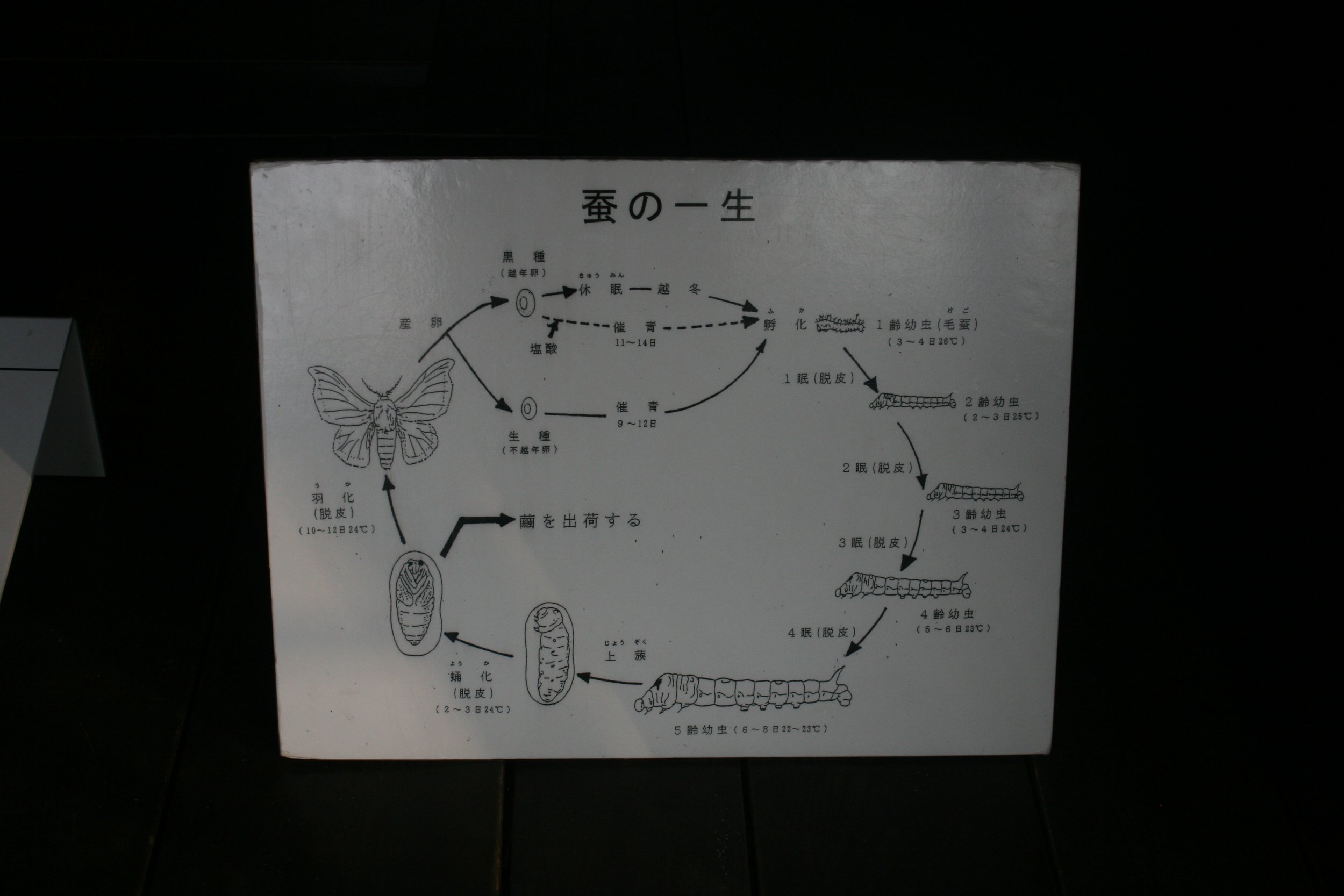

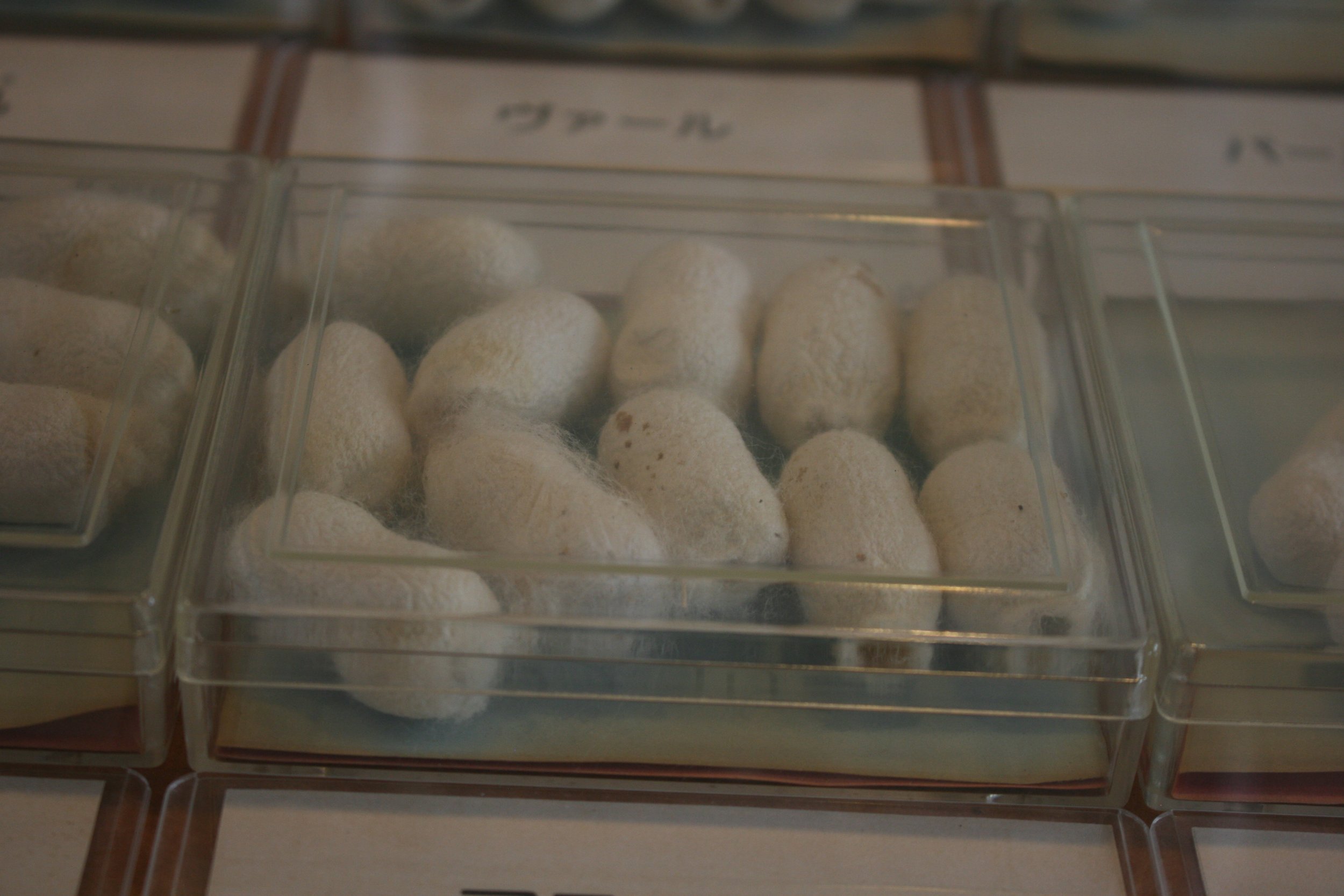

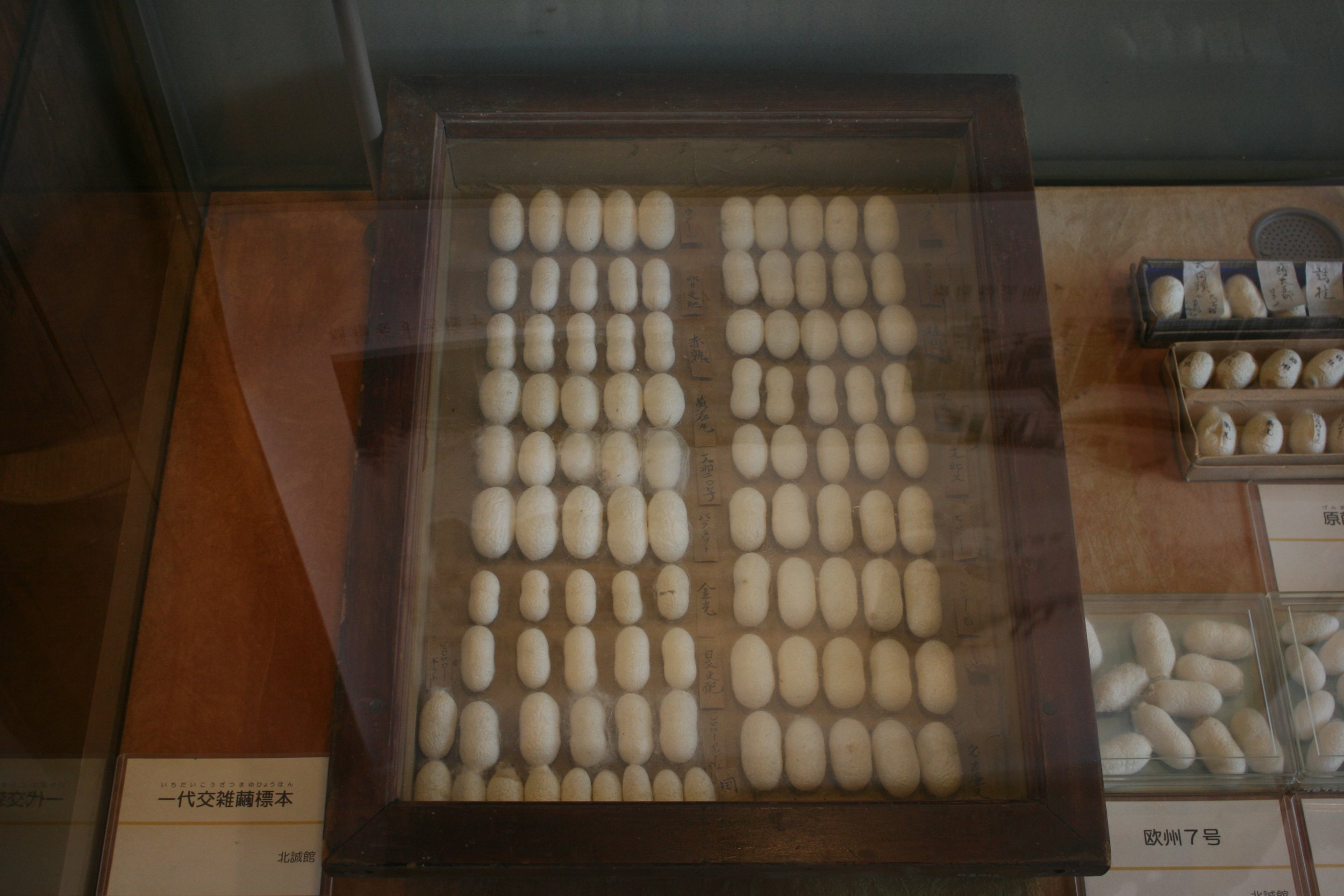

This map of Hokkaido shows the number of households engaged in sericulture (the cultivation of silkworms to produce silk) in Hokkaido in 1909. I found it in the silkworm house in the Historical Village of Hokkaido, a series of buildings recreated to resemble those of traditional Hokkaido; off season, it was a ghost town, and we had the entire “village” to ourselves.

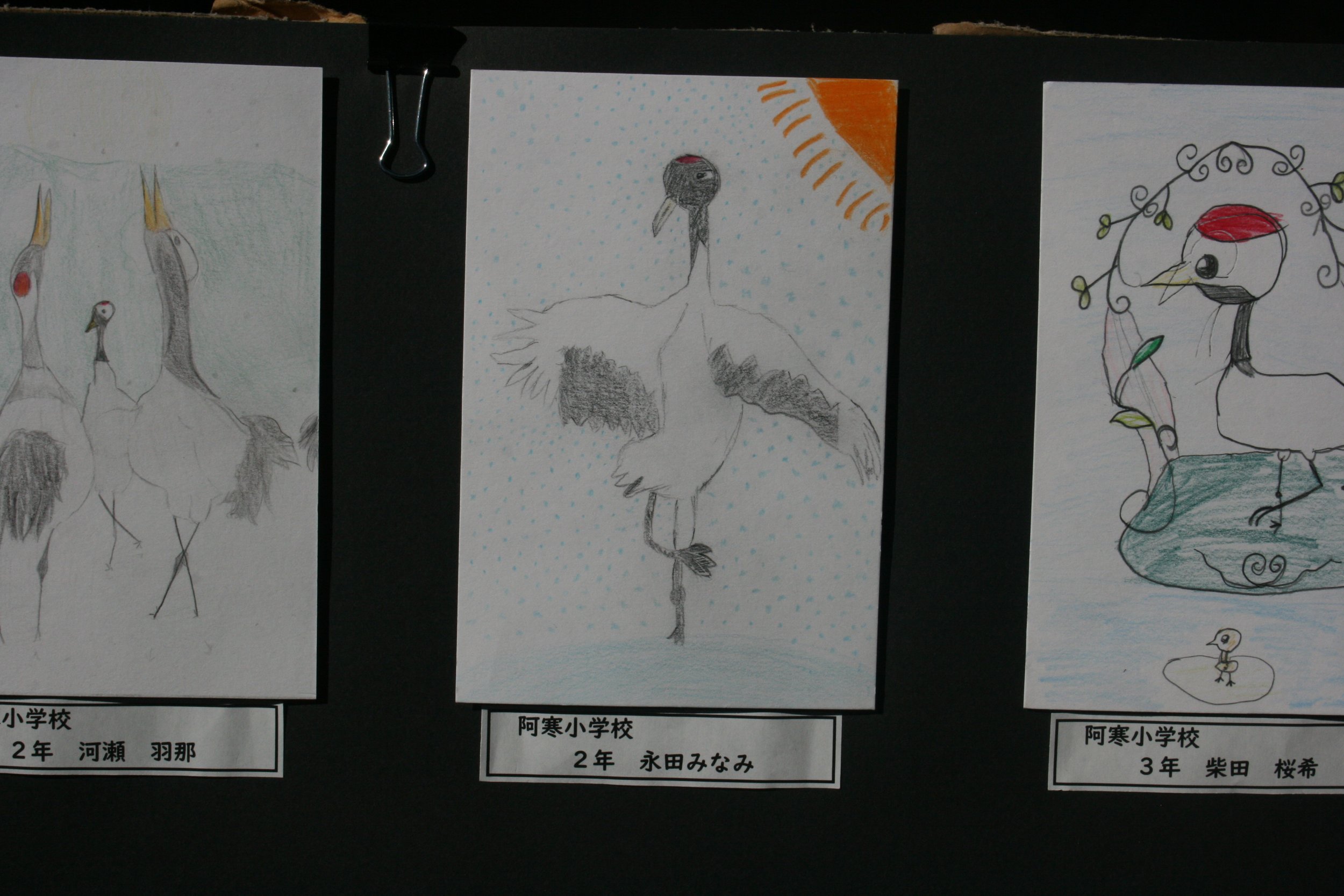

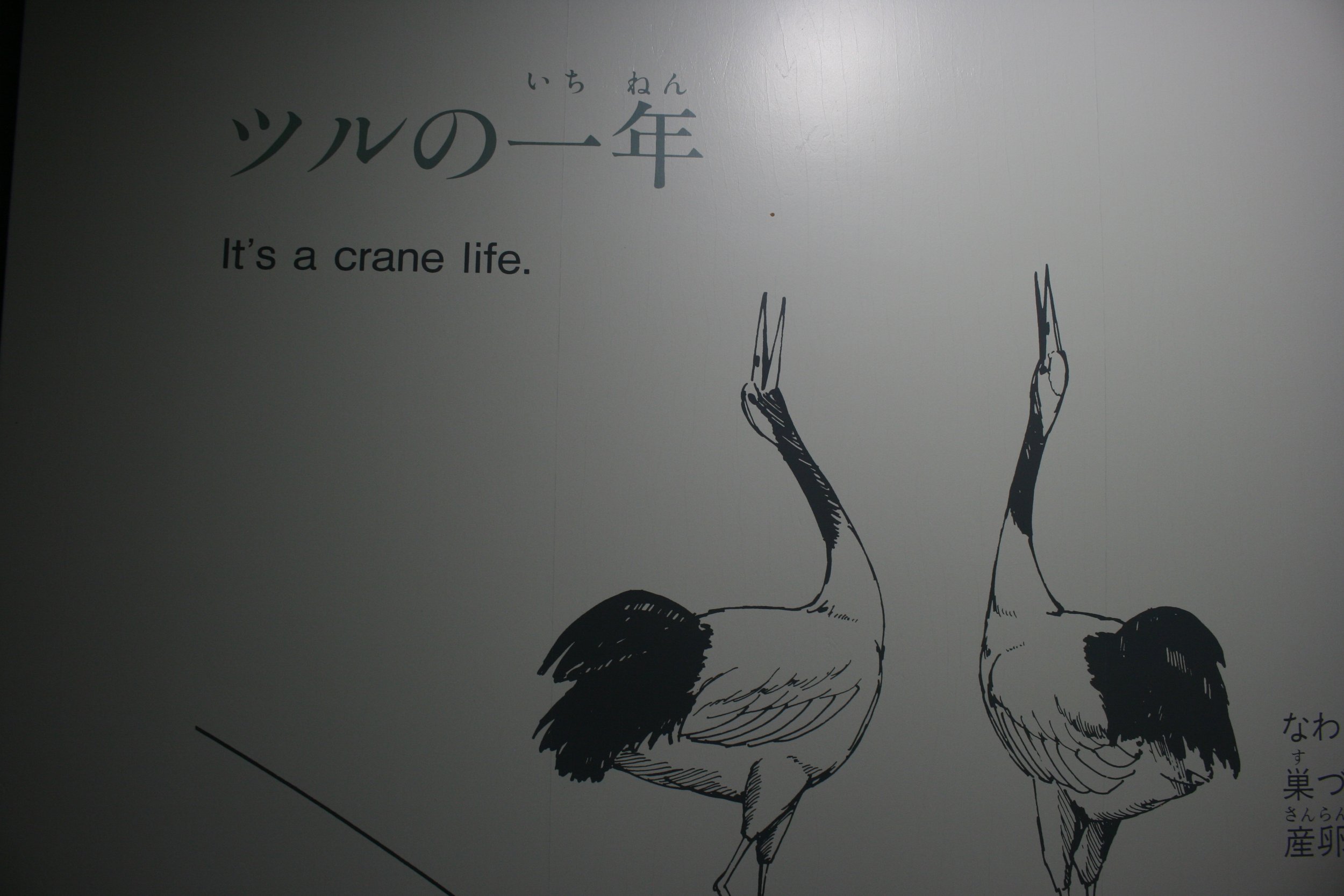

My first day in Hokkaido was in Kushiro, on the eastern side of the island. Kushiro is a port city situated on marshland, and one of the things it is best known for are the Japanese cranes that dwell there. My first stop on arrival was the Akan International Crane Center, where my companions and I wandered about among the birds. The light reflecting off the snow was so bright that I could barely keep my eyes open. But, standing in the shade, I spent some time observing the cranes. I was enamored by how they picked their way across the snow; in my notes, I wrote: “They lift their rear foot and collapse the talons like lifting a splayed napkin from a tabletop. Then spread their toes as they touch down forward, seeming to test or grasp the snow.” It was rather hypnotizing.

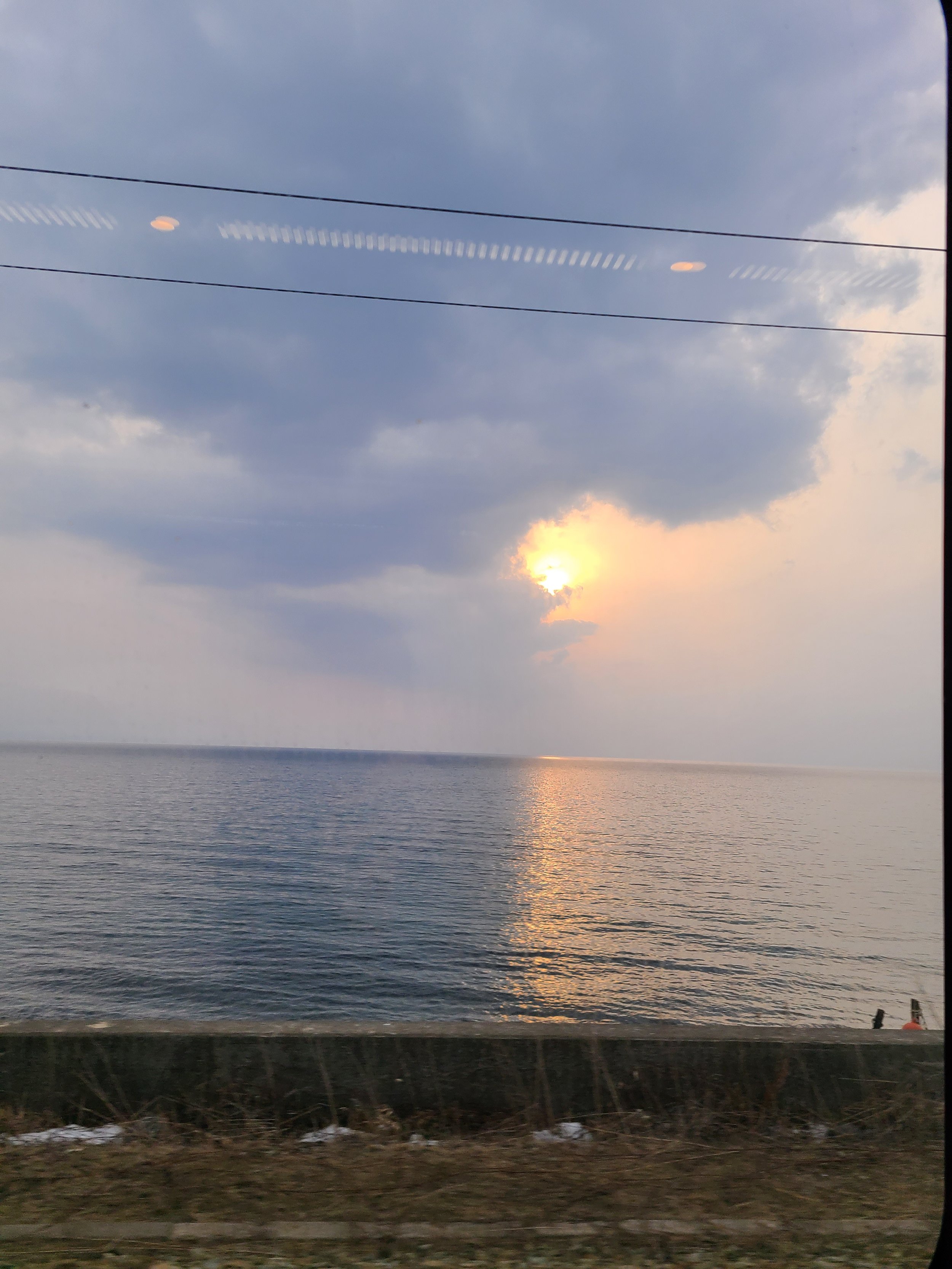

We took a bus into town, where we had lunch and wandered the streets. We crossed Nusamai Bridge (reviewers online say: “it’s just a bridge”), hiked up an observation deck to look down on the harbor, and navigated through “The Hills” of Kushiro to reach the Kushirosaki Lighthouse, where we saw, on the ridgeline, some beast trotting furtively along. A fox, or perhaps a dog, regarding us. A few more steps took us to the edge of the ocean, which felt cold and vast to look at. I thought of the Haruki Murakami short story, “UFO in Kushiro,” and appreciated why he chose this location as a site of alienation and discovery.

That evening, we took a train from Kushiro to Sapporo, where the annual snow festival had recently concluded. In the park where the festival takes place, we saw an enormous mound of snow. One of my travel companions noted that perhaps this was where all the snow sculptures had been impounded at the end of the festival. It was definitely a lot of snow.

Our day in Sapporo began at the Hokkaido Jingu shrine, where I wrote: “Snow dripping from trees in the sunlight and silence — I'm thinking how the site makes use of how things naturally happen — no one ‘designed’ this, but it feels intended and certainly appreciated.” It was beautiful! I was charmed by the snowy paths that felt out of a fairy story, and, yes, by the way trees just seemed to grow in the most pleasing places and views were framed as if by chance. I was delighted by a group of snow removal vehicles that buzzed about like toys on the shrine grounds. And as we walked out, that moment of snow dripping from the trees made me feel as though time had been suspended.

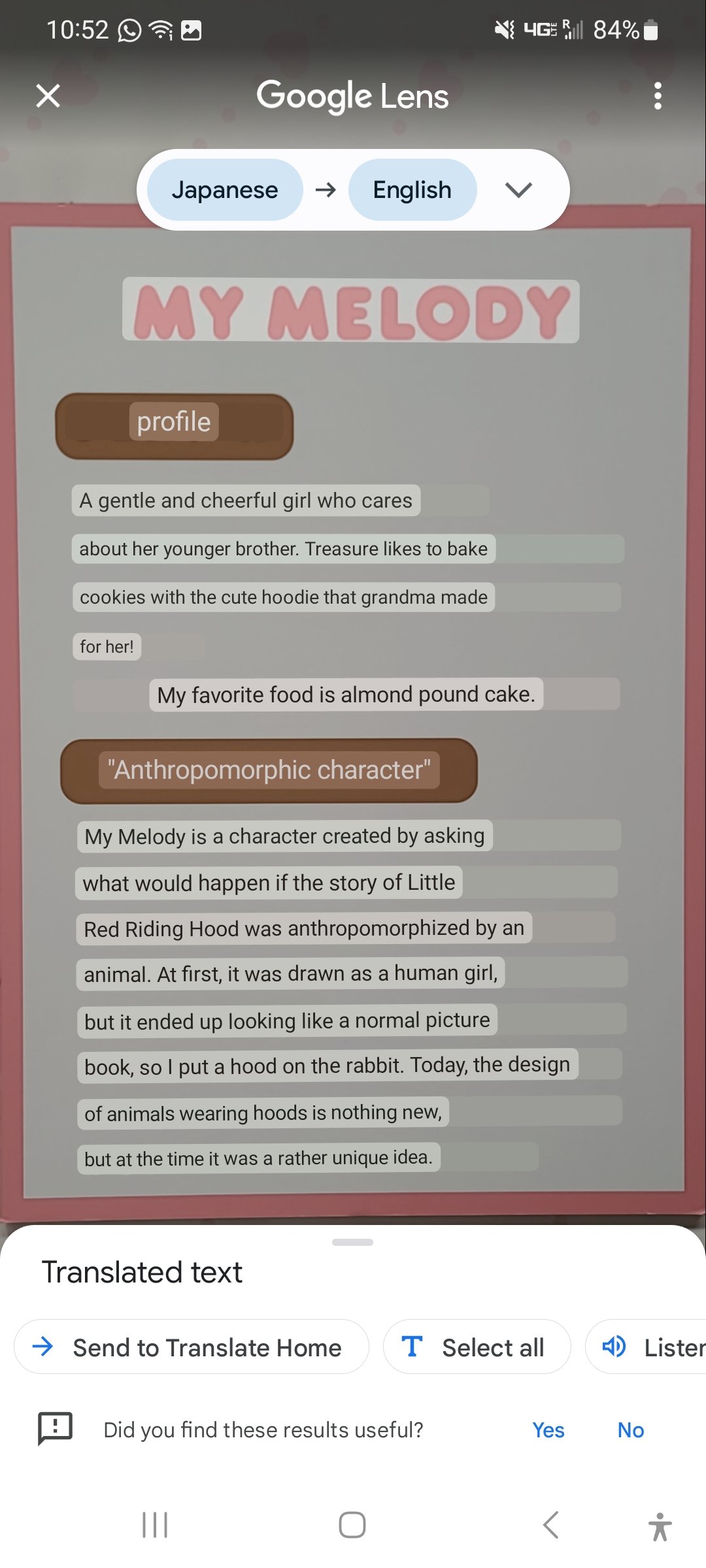

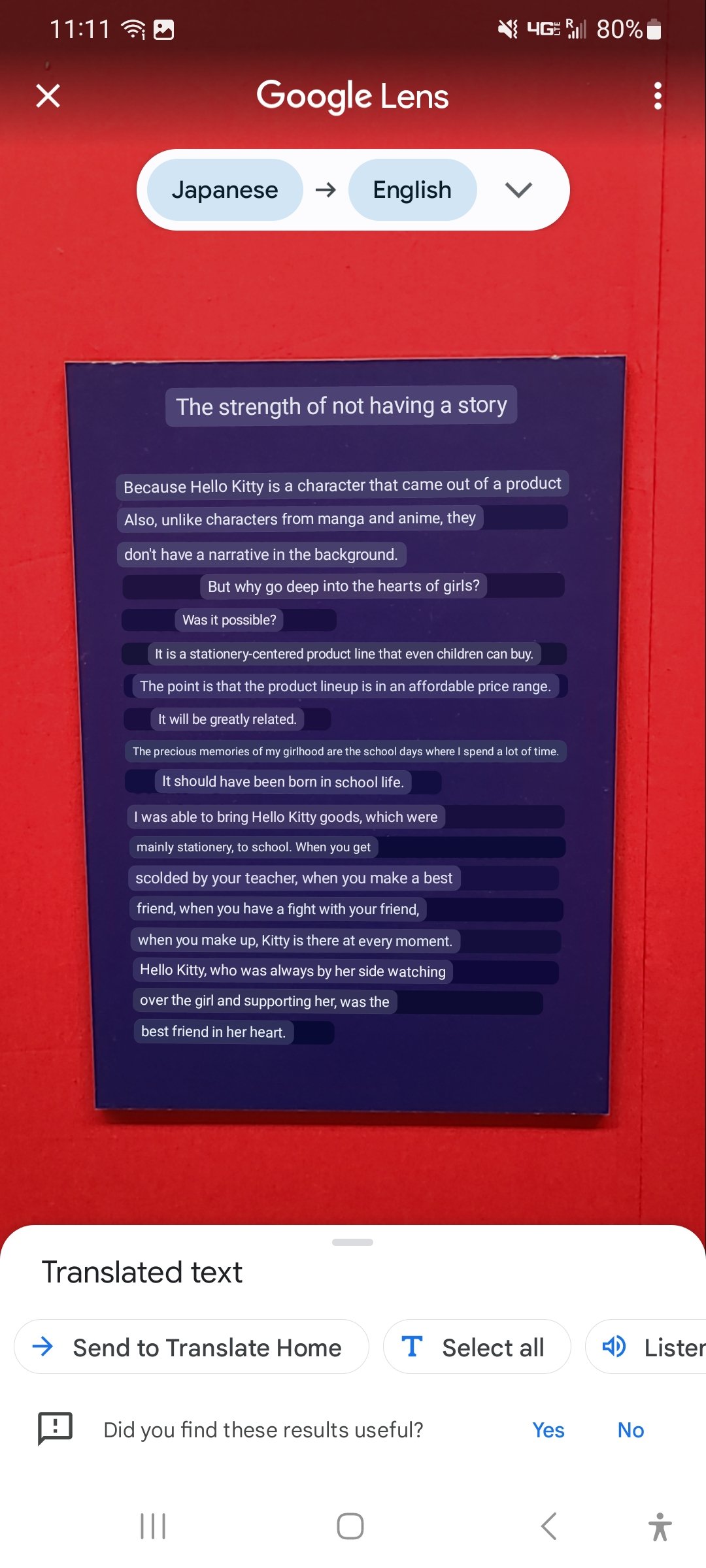

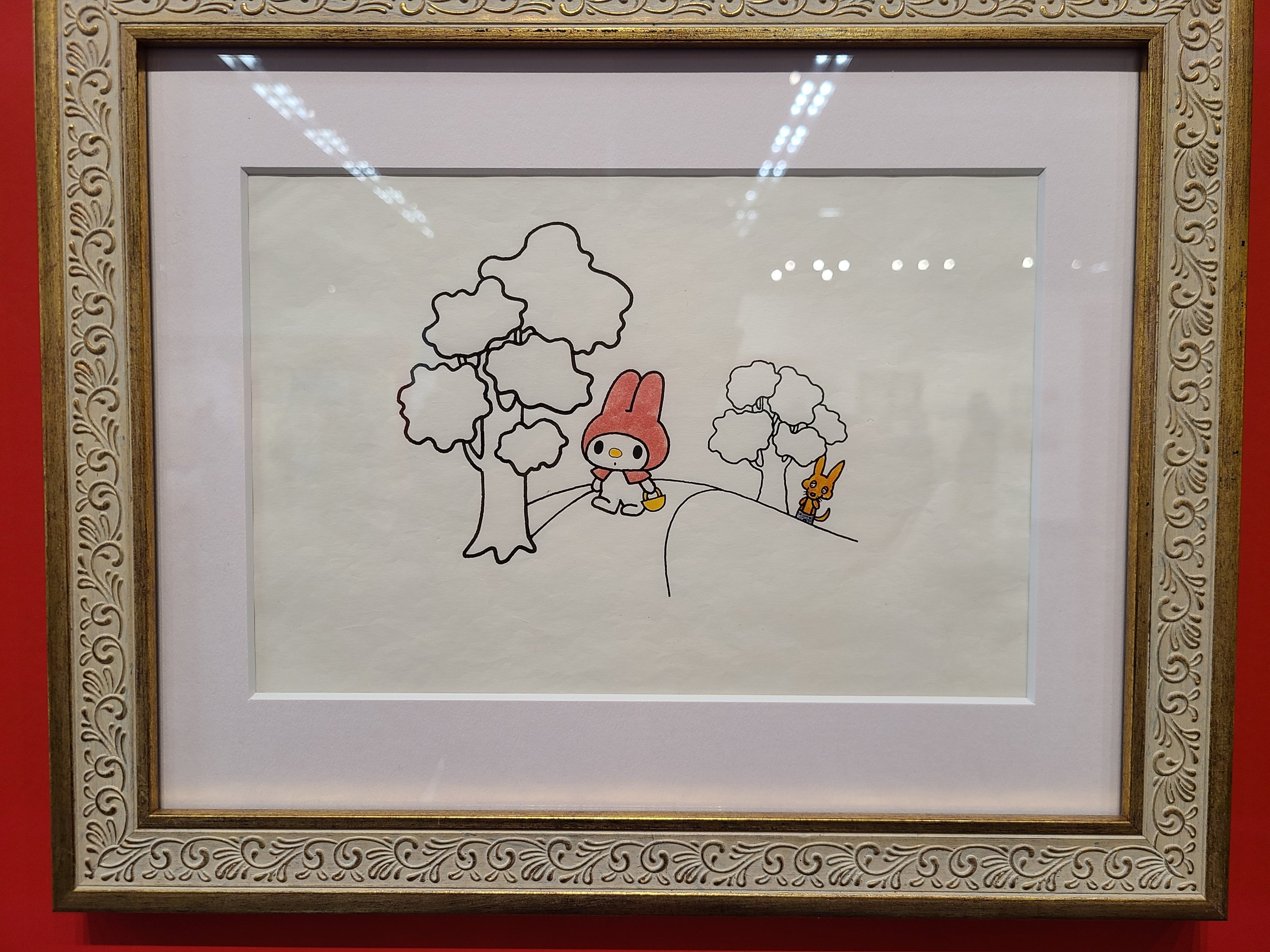

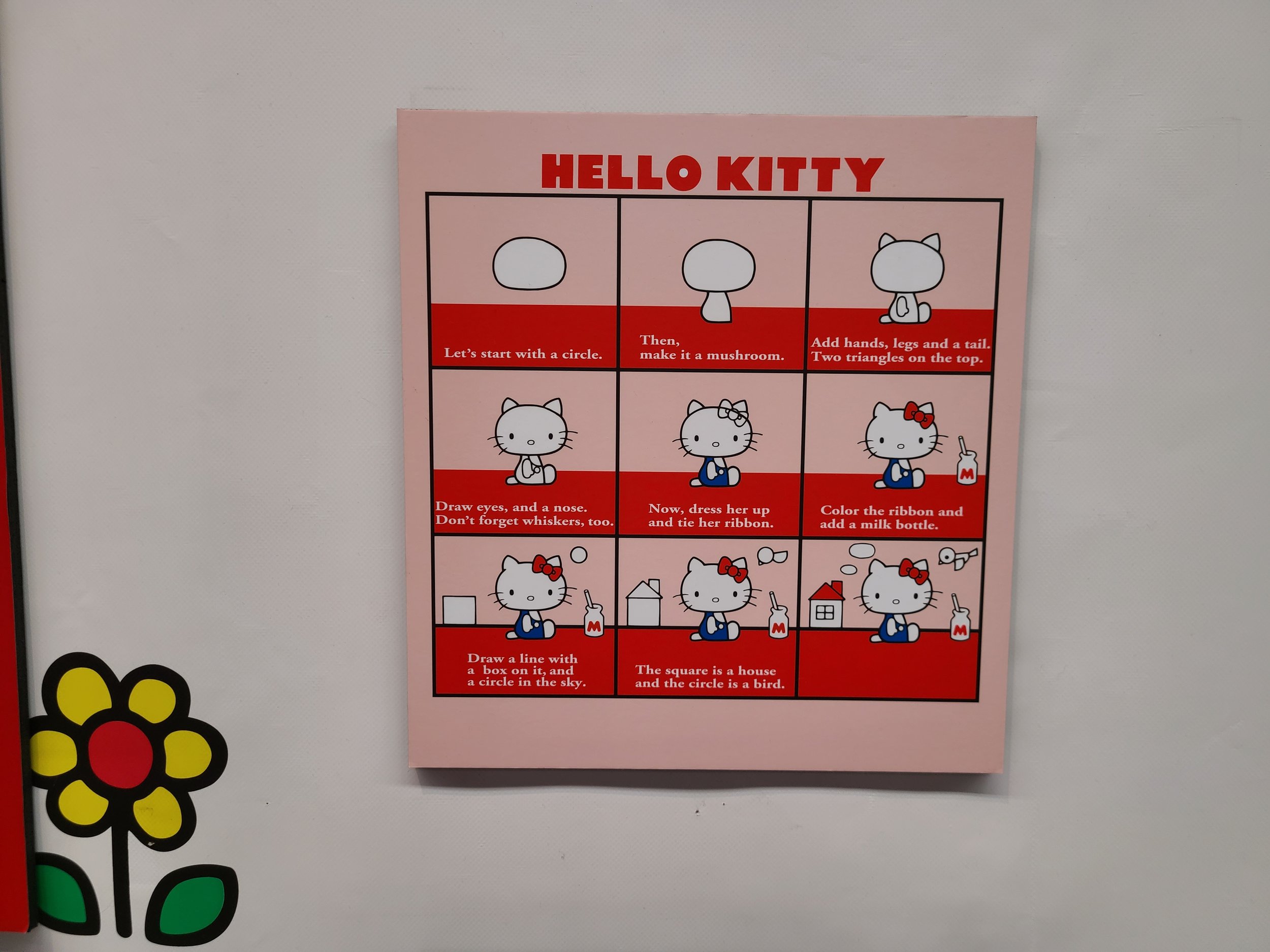

At the Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, we saw an exhibition titled “Sanrio: The Beginning of Kawaii.” Kawaii (“cute”) culture is a well known aesthetic in Japan, and I was grateful for the opportunity to see how the Sanrio company — the creators of Hello Kitty, among other popular characters — had channeled and contributed to it. I was especially taken with some of the early characters, predating Hello Kitty. What was it about them that gave the company confidence to build a business model around marketing these characters to a wide audience? In my notes, I wrote, “I am most reflective of the question of what gives a drawn character an ‘it’ factor – and what that factor entails; my initial interpretation was that they need a combination of specificity and vagueness that gestures toward a fully inhabited world but allows the viewer to insert and project their own ideas. It worked on me!” I’m still thinking about this: about the artists who came up with those initial designs, and what they — and others — saw in the characters they’d drawn.

We walked through the campus of Hokkaido University, where the snow was so deep it had buried some of the bicycles students had left behind over the winter break. Then we trekked to the Historical Village of Hokkaido, where I saw the silkworm house, among other old buildings. There were some fun translations of Japanese into English. I enjoyed learning about “indolent larvae.”

The next morning, we took a train from Sapporo to Shiraoi, where we stopped in at the Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park. The Ainu are a group of indigenous people who lived — and still live — in Hokkaido and nearby areas. The museum featured their history and examples of their artwork. I found several items that captured my interest, including wooden pacifiers for babies (splinters!), a tray of prepared food for loved ones who’d passed away that reminded me of a lunch box, and an exquisitely carved fishing knife. I had some gripes; one bit of wall text said, “Ainu cooked using locally sourced ingredients,” as though the Ainu would have ever labeled their food with such anachronistic language. It was difficult to get a grasp on the museum’s point of view, but I appreciated the opportunity to learn about a culture with which I was unfamiliar. Many Ainu houses had sacred windows, through which holy objects could be passed, but which the household residents were forbidden to look at or out of. I found myself imagining having a window that one could never look through; such a rule must grant it great power, indeed. There were no photographs allowed in the museum, but the grounds, which were dominated by a frozen lake, were beautiful.

Our next train took us further down the coast to Noboribetsu, where we stopped at Hokkaido’s most famous onsen, or hot spring resort. In the traditional (gender segregated, no clothing other than a towel) bathing area, I got to sample the array of different baths: saline, sulfur, scalding, freezing, bubbling, pebbles underfoot and waterfalls above.

In my notes, I wrote: “A steam room that felt almost alien, the vapor so dense and acrid that it made my lips tingle, my eyes water, my lungs clench and burn. But I slowly adjusted. From the door, I could see two black chairs and a couple more blurred ones beyond, but the room was so thick with white mist that I genuinely couldn't see more than a couple of feet in front of me. It looked endless, depthless. I navigated along the wall, where the steam issued from metal cylinders threateningly radiant with heat. It turned out there were only two rows of three chairs — all too hot for me to touch, let alone imagine sitting in — but the small room had seemed vast. From the far corner, I could barely see the window panel in the door.”

There was an outdoor bath as well, from which one could look out at the snowy mountainside. For a few minutes, I was entirely alone, and I let my mind enter a reflective state. Combined with the physical sensations of the baths, it felt restorative, even transformational.

No photos in the baths, obviously, but I snapped one from the elevator: the building was essentially vacant when I was there, the only staff member present being a woman who handed towels to ticket-holders who had passed through the quiet corridors to reach the changing rooms. But outside, I got a few glimpses of strange vapors issuing from fissures in the ground and saw statues of what one of my travel companions told me were “yukijin,” snow demons that patrol Noboribetsu fending off evil spirits with their heavy clubs.

Our last train, that evening, took us further along the coast to Hakodate, where we passed through a tunnel to leave Hokkaido and enter the Tohoku region on the main island of Honshu. From the train, we had views of snow at the edge of the water.