Sound of shoe on stone

Travel notes from Tohoku

After traveling in Hokkaido, I took a train across the channel to Japan’s largest island, Honshu, and into the Tohoku Region.

The Tohoku region, via Wiki image

I made the city of Sendai my home base in Tohoku. With a population of about a million people, it is the twelfth largest city in Japan.

My first stop was the Zuihoden Mausoleum, which lies at the summit of a hill. The ascent up a series of stone steps granted the space an apt sense of remove. A museum featured some morbidly charming analysis of the buried man’s remains: the dimensions of his skull were compared to those of other famous figures, and a footprint from “a worker who was in the ceiling of the Zennoden tomb” had the air of a specimen of natural history, like a dinosaur print fossilized in clay.

Outside, the burial site was ringed by a footpath through towering cedars. I was quite taken with a paving stone marked as “the ‘looks like skate’ stone.” They’re right; it does!

After lunch, I headed to the Miyagi Museum of Art, which had several exhibitions running. My favorite was “Sato Churyo: Rereading Three Masterpieces,” which focused on the sculptor Sato Churyo. I like museum shows that narrow one’s focus, so I was grateful for the opportunity to study specific pieces. “Man of Gunma” is a sculpture in the Western style (think Rodin) that depicts the head of a man with Japanese features. It has been heralded as one of the great feats of modern Japanese sculpture, and an example of a non-Western artist adopting Western techniques to depict people from his own culture.

“Man of Gunma” (1952), Sato Churyo

My personal favorite was “Hat, Summer,” which features a woman whose gaze is hidden beneath the wide brim of a summer hat. In my notes, I wrote, “I really like how the hat brim creates a genuine shadow… The real shadow on a figurative sculpture seems to blur representation and reality. It brings summer sun into the scene, even indoors! Who is this woman? She surely has ‘it’. “

“Hat, Summer,” Sato Churyo

Elsewhere in the museum, I saw some other excellent Sato Churyo sculptures, as well as a themed exhibition on snow — an ukiyo-e woodblock print of two women walking through snowfall with parasols made me think of the woman with the hat, and how depicting a covering (hat, umbrella) gestures toward the interiority of the subject, creating an intriguing sort of “cone of subjectivity” around them — and another on children’s books, where I enjoyed the panels from “Adventures of PEE, an excursion boat.”

I spent the afternoon at the Osaki Hachimangu Shrine and Rinnoji Temple, with its beautiful and contemplative Japanese garden. The thought came to me that I would have liked to visit it across several seasons, to see the changes in foliage and the different angles of light.

The following day, I took a local train from Sendai to Yamadera, the site of a temple complex atop a high hill. Yamadera is a popular place to view autumn leaves, and it appears to be less frequented in the winter; when I arrived, there was scarcely anyone around. The ascent to the summit comprises 1,000 stairs, and I made this journey in relative silence. In my notes, I wrote: “Snow falling faintly and faintly falling. Crows cawing. Sound of shoe on stone.”

Yamadera is so old that the site is documented as having undergone a restoration in the 1300s. The accumulation of those years is evident on the path: in practically every corner of the trail were tucked away small shrines and stone memorials, each with their particular meanings and practices. Of note, there is a haiku by the poet Basho buried on the mountain; one of his admirers placed it there in honor of his visit to Yamadera. I tried to imagine that day — one day out of the many thousands that have passed here — when an individual buried something to memorialize another individual. Then I wondered: what is the most recent addition to these memorials? Is the place still, even now, being revised, or has it calcified? The only things I saw anyone leave behind were coins.

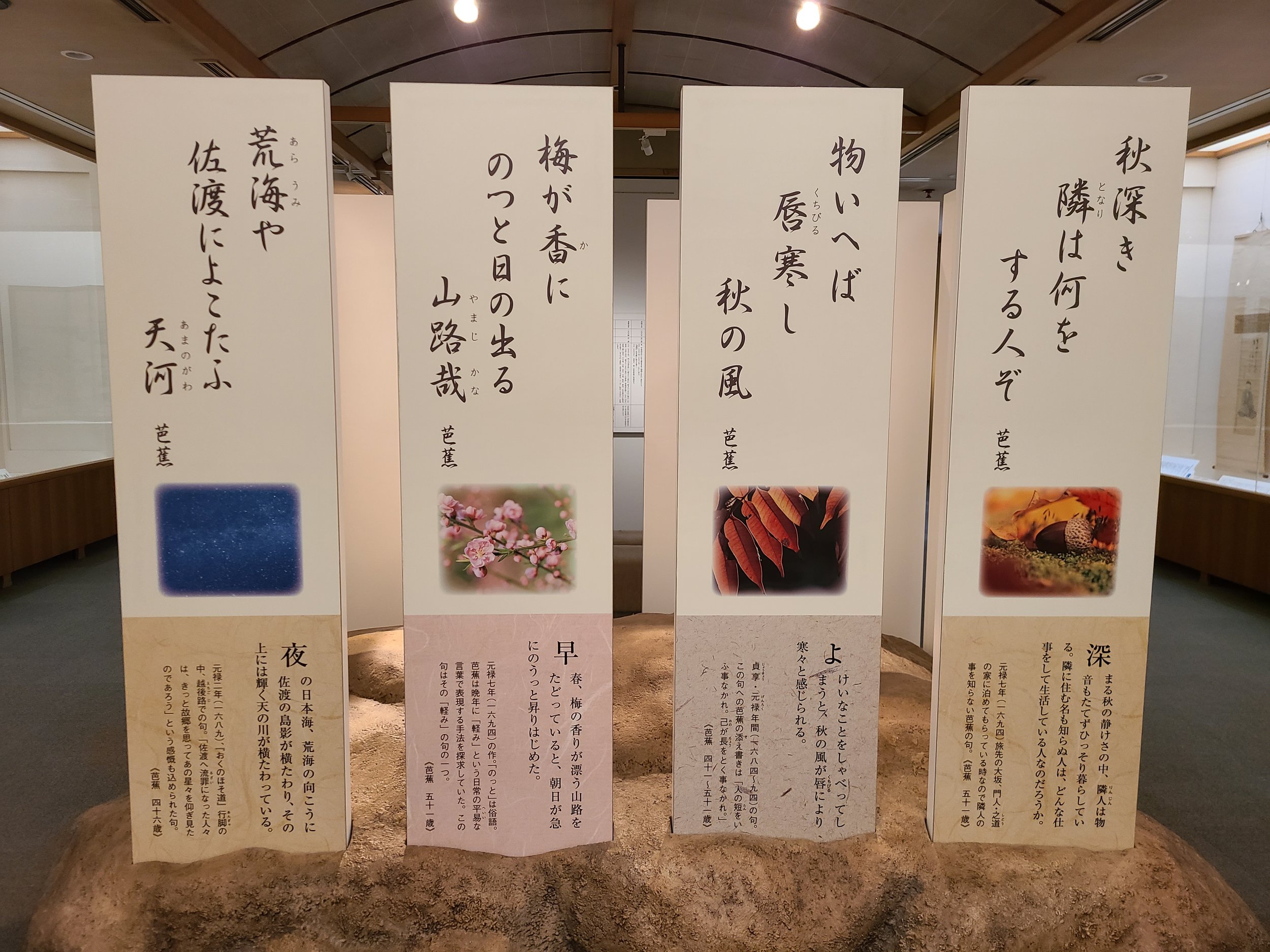

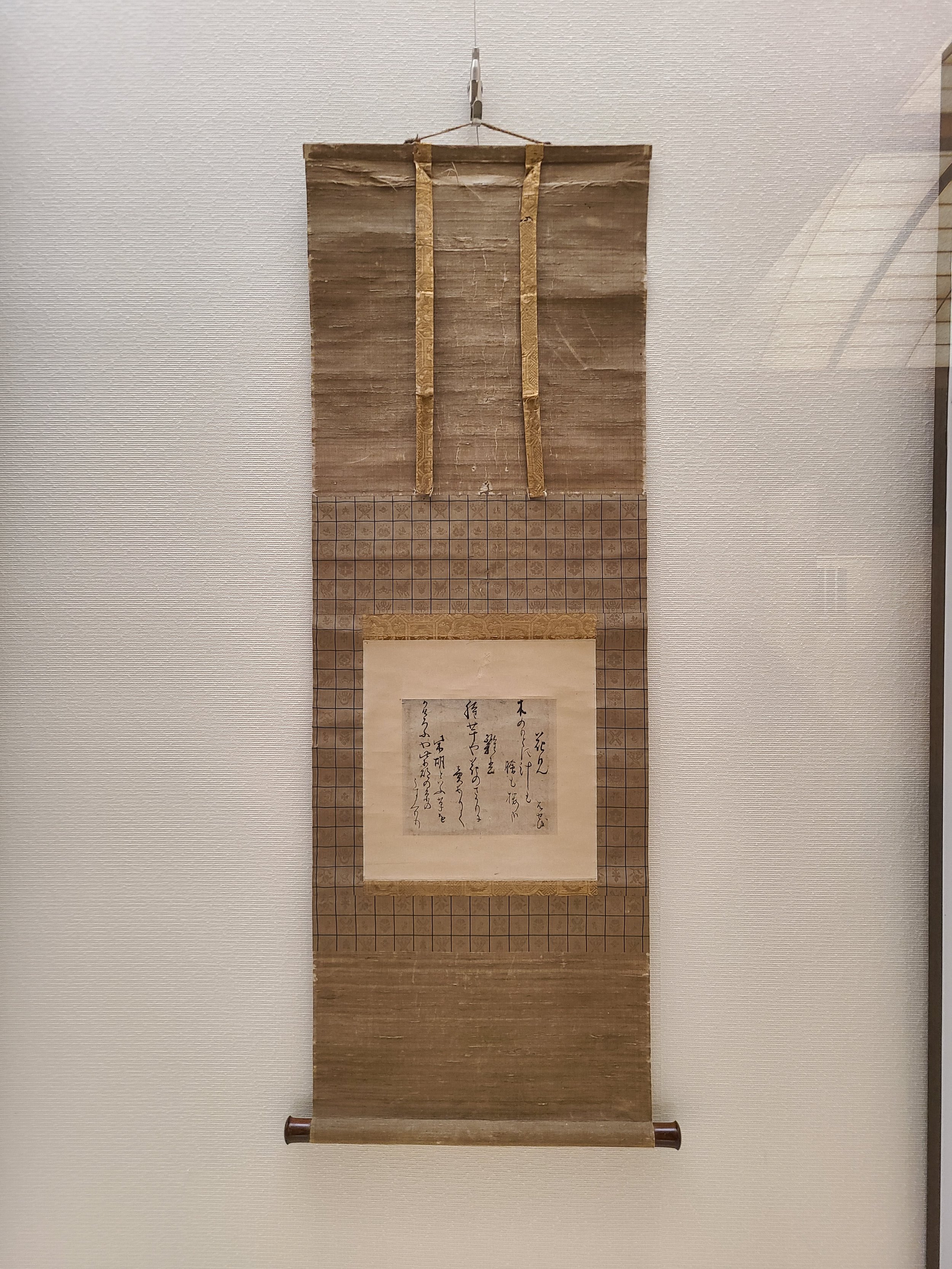

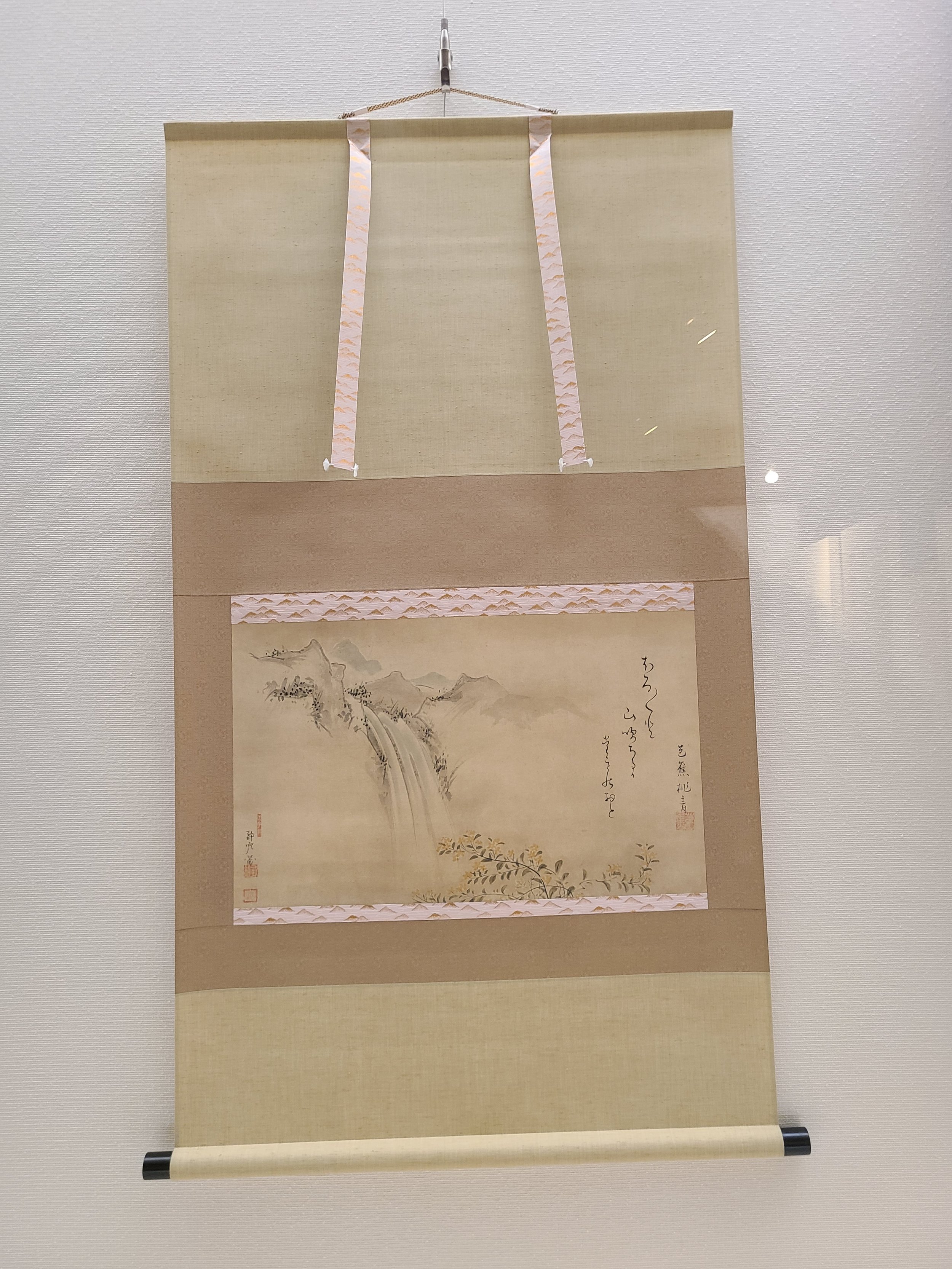

At the base of the mountain is the Basho Museum, dedicated to the life and work of the poet most famous for his haiku. I was grateful to see poetry rendered with such visual impact. Some of the haiku were painted on scrolls alongside illustrations. The quality of the Japanese kanji characters is itself illustrative, and it made me want to learn enough Japanese to be able to read these poems in their original context. The translations were beautiful in their own right.

All in all, it was an enriching visit made all the more special by the fact that I seemed to be the only one there. I took a train back through Sendai on my way south, to the region of Kanto.